It may well be a fool's errand for a finite being (mortal; flesh and blood) to seek after and try to know the infinite Creator, but in each generation there are a handful who try their best. In the closing lines of Job in today's Bible Study group, there is the puzzling remark uttered by God about the 3 friends who quote scripture and Jewish beliefs at Job: God declares that Job is righteous even in his misery, but that the friends are not. Furthermore, Job apologizes for having been asking the wrong question of God, all along, "why me, LORD"?

What seems to be going on in the story is that Job submits, accepts, embraces his utter humility and absence of (self) pride before his maker; he will not forsake God, no matter what. In this totally vulnerable condition, there is nothing separating the man from God. Nothing stands between them and words completely fail in such up-close-and-personal encounters. Words (logos) and by extension, logic, is central to being human; central also to sin and distraction and false certainties. God is beyond words and beyond the space between lines of text or between syllables of spoken communication. Thought and language go closely together (and writing, by extension). But God is far bigger than that.

One conclusion, then, is that we will go on relying on words to relate to each other and to know God. But we should hold onto those words lightly or loosely, since they are far from perfect and carry the risk of instilling a false sense of control and comprehending (apprehending) God's will. In a simple spectrum, the cerebral use of words for Protestants puts faith is precise word use. The repeated and ritualistic use of words in Catholic Mass gives some breathing room for other meanings that seep through and within the syllables spoken by all. Then the ecstatic encounters of "God Winks" and "God moments" (such as the trance like experience of Whirling Dervishes of the Sufi branch of Islam) or "burning bush" encounters dispense with verbal elements entirely. If the cerebral trust in logic is one extreme and the ecstatic experience is the other extreme, then perhaps somewhere in the middle is best: make use of words, but do so with a light touch or a loose grip so that the words may move a bit.

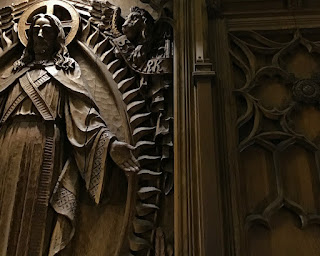

This photo from above the altar at the First Congregational Church of Grand Rapids, Michigan shows the carver or carvers' skill in shaping the wood into this figure and his surroundings. Because people can peer at the art without using words, it offers a visual way to wonder at God's wonder; to hold the teachings and conversations loosely - firmly believing but also willing to allow the ideas to wiggle, too. If the Pharisees dwell on the letter of The Law, and the Sufi dervishes dwell on the spirit of The Law (God and our relationships with the Creator), then perhaps the average person can do well by seeking a middle ground: know scripture, but see beyond the page to know fellow seekers and to recognize God every day in the many forms of Earthly life.

No comments:

Post a Comment